Dan TynanTech ColumnistMay 4, 2015

I was in the lobby of the Intercontinental Hotel in San Francisco, milling around with three dozen other crusty tech journalists waiting for a turn to enter the matrix. It was clear from the outset we were not to be trusted.

(Microsoft)

We’d been invited to an exclusive 90-minute dive into the inner workings of the HoloLens, the augmented reality headset Microsoft revealed last January to great acclaim. Not only would we get the chance to interact with virtual objects in the real world, we’d also learn how to program the HoloLens ourselves.

Read: I Try Microsoft’s Crazy HoloLens

But first we had to make it past security. It wasn’t going to be easy. I couldn’t walk six feet without bumping a beefy guy in a dark-blue suit talking into his wrist. It felt like I was attending a Beyonce concert with Sasha and Malia Obama.

The HoloLens promised to be an awesome experience. I just had to avoid getting arrested first.

Eager pupils

From the lobby, a posse of Microsoft PR pros in light-blue polos herded us into elevators in groups of six and took us to the HoloLens demonstration area on fifth floor.

At the registration desk, a young woman in a blue hoodie handed each of us a plastic ID card on a lanyard, a hoodie, and a numbered key. The keys were for bus-station style lockers that had been set up in the hallway of the Intercontinental. I was instructed to put all my electronics into the locker and bring only a pen and a pad of paper into the room.

The HoloLens demo from Microsoft’s Build 2015 conference (Chris Burns/Youtube).

Beyond the lockers, a muscular guard in a blue polo shirt was separating the journalists into pairs. Each pair, he explained, would be accompanied by a “mentor” — a Microsoft employee who would guide us through the program and, presumably, keep us from conducting industrial espionage.

As we waited on line to enter the HoloLens sanctum, a bespectacled nerd approached me holding a device that looked like a 3D View-Master designed by the KGB. It was, he said, a “pupilometer,” designed to measure the distance between my eyes, which was necessary to calibrate the HoloLens. When I peered inside, I could see a single point of light in the infinite distance.

(It didn’t feel like Microsoft was attempting to reprogram my brain. Have I mentioned just how much I love Satya Nadella?)

It turns out my pupils are precisely 66.5 millimeters apart. “Is that good?” I asked. He said it was above average, a fact I found stupidly satisfying. He wrote the number down on a sticky note and attached it to my ID card.

Holo goodbye

We were led into a cordoned-off area and introduced to our mentor, Alex. He looked to be about 19 years old, had a Beatles haircut circa 1964, and spoke in heavily accented Eastern Euro English. Alex told us he was born in Belarus.

The area was filled with industrial-sized jars of snacks and buckets of drinks on ice, as well as about a dozen more security guards wearing earbuds with squiggly wires disappearing down the backs of their necks. I managed to grab a handful of M&Ms and two gulps of water before Alex hustled us into the room.

“No drink inside,” Alex said sternly. “Very sorry.”

(Microsoft)

We entered a large conference room set up like a series of faux living rooms with couches and coffee tables, surrounded by desks with keyboards, mice, and big displays. I took a seat at one of the desks next to Alex.

Our exceedingly enthusiastic host, Brandon Bray, stood on a raised platform in the center of the room and explained that we had just enrolled in the “Holograph Academy Express.” The normal Holograph Academy took four hours to teach developers the basics of programming for the HoloLens, Bray said; we’d be completing our crash course in roughly 90 minutes.

During that time, we’d learn how to manipulate the three modes of interacting with the HoloLens — gaze, gesture, and voice input — and create holographic programs that could run on any Windows device.

“All holograms can be universal Windows apps,” Bray gushed. “And all Windows apps can be holograms.”

Gesture aerobics

It was at that moment I realized that, instead of being safely secured in a bus locker, my phone was still tucked in my back pocket. I had a moment of panic, followed by a brief moral dilemma: Should I try to surreptitiously film the proceedings on my iPhone under the suspicious eyes of my mop-topped mentor?

Visions of being hustled out of the room by a pair of security guards the size of Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson ran through my brain.

Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson (IMDB).

Stealthily, I pulled the phone out of my pocket, turned the ringer volume to low, and hid it inside my sock, hoping no would try to call me and that I would live to see my family again.

Then it was time for “gesture aerobics.” Bray urged everyone to stand up and led us through a quick warmup where we practiced gazing at the floor and the ceiling, wiggled our fingers in the air like we were flipping off a light switch, and repeated the word “reset.”

“Congratulations,” he proclaimed, “You are now qualified to create your Holoworlds.”

My fellow scruffy journalists applauded.

Project Origami unfolds

Our first step was to open a browser interface and enter our pupilometer number, which was transmitted to a HoloLens attached to each computer via a USB cable.

Bray explained that since we had only 90 minutes, most of the heavy lifting had already been done for us. The 3D objects and scripts had been created and loaded into Visual Studio; our job would be to piece them all together, kind of like building The Millennium Falcon from a LEGO Star Wars kit.

If anything went wrong, Alex was there to make sure we clicked the appropriate items at the appropriate times — and to keep us from breaking the damned things.

Thus began Project Origami. We started by dragging and dropping the “stage” onto the workspace in Visual Studio and assigning XYZ coordinates to tell the HoloLens where to display it. We exported the stage to the Unity game-development engine and then loaded it onto the lenses.

As I did this, Alex held my HoloLens in the air and pointed it at the coffee table behind us. That way, he said, the stage would appear to be sitting on the table, about 2 meters in front of me.

He detached the glasses and handed them to me. They looked like a pair of industrial-strength ski googles, but felt noticeably lighter than any of the other virtual reality headsets I’ve tried on.

(Microsoft/YouTube)

The HoloLens consists of an inner ring that fits over your forehead, and an outer ring containing the electronics, which flips up like a visor. Bray instructed us to put the first ring over our heads “like you’re putting on a baseball cap,” turn the knob on the back until we had a tight fit, then swing the 3D display down over our field of vision.

When I looked up, I discovered a surreal 3D image hovering over the coffee table: Two yellow paper airlines were balanced at an angle on stacks of paper cubes, which were themselves perched on top of a large legal notepad. Two paper spheres floated above the scene; one looked like a crumpled ball of newspaper and the other looked like the Everlasting Gobstopper from Willy Wonka. This was the “stage.”

If you squint, these look vaguely like some of the virtual objects in Project Origami (Aaron Muszalski, Dan Morelle, and Zoomar/Flickr).

Beyond this surreal vision, I could see the ghostly outlines of my fellow scruffy journalists through the glasses and hear the person next to me chatting with her mentor.

I poked at the vision in front of me; my finger passed harmlessly through it.

Beyond the 4th dimension

Then we took off the glasses, returned to Visual Studio, and added gaze, gesture, and voice recognition to the stage. Our gaze interface was a red hexagonal ring we positioned by staring at the virtual objects we wanted to control; Bray called this “the donut.” The gesture was a small movement of my index finger, kind of like clicking a mouse button (the “airtap”).

We downloaded the new commands and put the glasses back on. Now when I stared at one ball the donut appeared over it; flipping my finger caused it to drop down onto the surface of the paper airplane, bounce off the edge of the legal pad, and disappear into the 4th dimension, never to be seen again. Saying the word “reset” brought the balls back into position so we could repeat the experiment.

Then we added another voice command, which Bray urged us to customize. Now I could cause the sphere to move by gazing at it and saying, “Drop it like it’s hot.” The next step was ambient sound: We attached a single line of code (“SpatialSound.play ‘ambience.wav’”) that added a cheesy Japanese soundtrack, the kind you’d hear in an airport sushi bar. The sound was location-aware; the closer I came to the stage, the louder it got.

Next was spatial mapping. We added a wireframe to the scene that automatically adhered to the real-world surfaces beneath the virtual one. Now when the ball dropped off the edge of the stage, it bounced off the wireframe covering the coffee table and onto my shoe. Then we removed the wireframe, so it looked as if the balls were reacting to the actual objects in the room. This is when the hairs on the back of my neck started to rise.

We added a command that let us tap on the stage, “lift” it with the donut, and place it anywhere else in the room. This didn’t work so well, but was cool nonetheless.

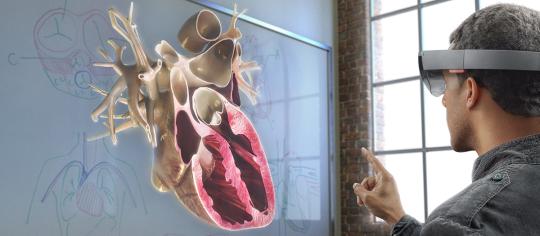

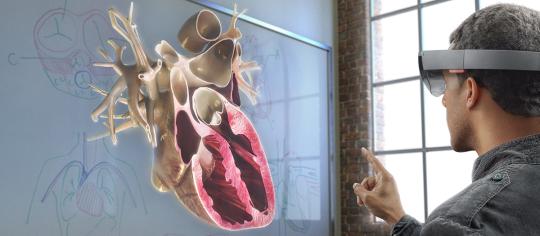

A virtual heart displayed via HoloLens (Case Western University/Microsoft).

For the grand finale, we added a script that caused the stage to explode when the ball landed, creating a virtual hole in the floor that revealed a subterranean 3D world.

It looked like a scene from Minecraft with the sharp edges sanded off. A red origami crane floated serenely between fluffy white clouds over green fields and twisty blue rivers. When I leaned far enough over the edge of the virtual hole, I could see the ball was still down there, rolling round.

Then I took off my glasses and watched a roomful of scruffy tech journalists leaning, crouching, poking, and tapping … nothing at all.

The revolution will be virtualized

Though impressive, my HoloLens experience was far from flawless. The vertical field of vision was extremely narrow; moving my head even slightly caused the Project Origami stage to disappear from view. Picking up the virtual stage and dropping it seemed to max out the hardware’s ability to render the image — it kept getting “stuck” on various pieces of furniture. And the cartoonish Project Origami was far less sophisticated than the virtual 3D models of bodies and buildings Microsoft displayed during the keynote address the day before.

On the other hand, I was navigating a friggin’ virtual world inside the real one. Hello 2015, your future has arrived.

As we went through our paces, I tried to pump Alex for information about the HoloLens. Every question I had about the hardware — like how many front-facing cameras it had (I counted at least six) or how it did eye tracking — was met with the same response.

“Information was yesterday presented in keynote,” he said. “I am not more to speak of it.”

The woman on stage during the Build 2015 demo is real; the dino skull can only be seen via the HoloLens (Dan Tynan/Yahoo Tech).

The secrecy and security surrounding the HoloLens shows just how important this device is to restoring Microsoft’s mojo. The idea that the world around you can be your computer display — or that you can essentially bring your own holodeck wherever you go — is pretty compelling. The notion that Microsoft Windows is the engine that could make this happen would have seemed laughable less than a year ago. And yet, that future seems to be here — or at least, it will be, if and when HoloLens becomes commercially available.

At the end, Bray urged his audience of crusty old journalists to shout, “We love holograms!” — which they did with the kind of enthusiasm you usually only see from twenty-somethings at Apple events.

Maybe that pupilometer was more effective than I thought.

I was in the lobby of the Intercontinental Hotel in San Francisco, milling around with three dozen other crusty tech journalists waiting for a turn to enter the matrix. It was clear from the outset we were not to be trusted.

(Microsoft)

We’d been invited to an exclusive 90-minute dive into the inner workings of the HoloLens, the augmented reality headset Microsoft revealed last January to great acclaim. Not only would we get the chance to interact with virtual objects in the real world, we’d also learn how to program the HoloLens ourselves.

Read: I Try Microsoft’s Crazy HoloLens

But first we had to make it past security. It wasn’t going to be easy. I couldn’t walk six feet without bumping a beefy guy in a dark-blue suit talking into his wrist. It felt like I was attending a Beyonce concert with Sasha and Malia Obama.

The HoloLens promised to be an awesome experience. I just had to avoid getting arrested first.

Eager pupils

From the lobby, a posse of Microsoft PR pros in light-blue polos herded us into elevators in groups of six and took us to the HoloLens demonstration area on fifth floor.

At the registration desk, a young woman in a blue hoodie handed each of us a plastic ID card on a lanyard, a hoodie, and a numbered key. The keys were for bus-station style lockers that had been set up in the hallway of the Intercontinental. I was instructed to put all my electronics into the locker and bring only a pen and a pad of paper into the room.

The HoloLens demo from Microsoft’s Build 2015 conference (Chris Burns/Youtube).

Beyond the lockers, a muscular guard in a blue polo shirt was separating the journalists into pairs. Each pair, he explained, would be accompanied by a “mentor” — a Microsoft employee who would guide us through the program and, presumably, keep us from conducting industrial espionage.

As we waited on line to enter the HoloLens sanctum, a bespectacled nerd approached me holding a device that looked like a 3D View-Master designed by the KGB. It was, he said, a “pupilometer,” designed to measure the distance between my eyes, which was necessary to calibrate the HoloLens. When I peered inside, I could see a single point of light in the infinite distance.

(It didn’t feel like Microsoft was attempting to reprogram my brain. Have I mentioned just how much I love Satya Nadella?)

It turns out my pupils are precisely 66.5 millimeters apart. “Is that good?” I asked. He said it was above average, a fact I found stupidly satisfying. He wrote the number down on a sticky note and attached it to my ID card.

Holo goodbye

We were led into a cordoned-off area and introduced to our mentor, Alex. He looked to be about 19 years old, had a Beatles haircut circa 1964, and spoke in heavily accented Eastern Euro English. Alex told us he was born in Belarus.

The area was filled with industrial-sized jars of snacks and buckets of drinks on ice, as well as about a dozen more security guards wearing earbuds with squiggly wires disappearing down the backs of their necks. I managed to grab a handful of M&Ms and two gulps of water before Alex hustled us into the room.

“No drink inside,” Alex said sternly. “Very sorry.”

We entered a large conference room set up like a series of faux living rooms with couches and coffee tables, surrounded by desks with keyboards, mice, and big displays. I took a seat at one of the desks next to Alex.

Our exceedingly enthusiastic host, Brandon Bray, stood on a raised platform in the center of the room and explained that we had just enrolled in the “Holograph Academy Express.” The normal Holograph Academy took four hours to teach developers the basics of programming for the HoloLens, Bray said; we’d be completing our crash course in roughly 90 minutes.

During that time, we’d learn how to manipulate the three modes of interacting with the HoloLens — gaze, gesture, and voice input — and create holographic programs that could run on any Windows device.

“All holograms can be universal Windows apps,” Bray gushed. “And all Windows apps can be holograms.”

Gesture aerobics

It was at that moment I realized that, instead of being safely secured in a bus locker, my phone was still tucked in my back pocket. I had a moment of panic, followed by a brief moral dilemma: Should I try to surreptitiously film the proceedings on my iPhone under the suspicious eyes of my mop-topped mentor?

Visions of being hustled out of the room by a pair of security guards the size of Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson ran through my brain.

Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson (IMDB).

Stealthily, I pulled the phone out of my pocket, turned the ringer volume to low, and hid it inside my sock, hoping no would try to call me and that I would live to see my family again.

Then it was time for “gesture aerobics.” Bray urged everyone to stand up and led us through a quick warmup where we practiced gazing at the floor and the ceiling, wiggled our fingers in the air like we were flipping off a light switch, and repeated the word “reset.”

“Congratulations,” he proclaimed, “You are now qualified to create your Holoworlds.”

My fellow scruffy journalists applauded.

Project Origami unfolds

Our first step was to open a browser interface and enter our pupilometer number, which was transmitted to a HoloLens attached to each computer via a USB cable.

Bray explained that since we had only 90 minutes, most of the heavy lifting had already been done for us. The 3D objects and scripts had been created and loaded into Visual Studio; our job would be to piece them all together, kind of like building The Millennium Falcon from a LEGO Star Wars kit.

If anything went wrong, Alex was there to make sure we clicked the appropriate items at the appropriate times — and to keep us from breaking the damned things.

Thus began Project Origami. We started by dragging and dropping the “stage” onto the workspace in Visual Studio and assigning XYZ coordinates to tell the HoloLens where to display it. We exported the stage to the Unity game-development engine and then loaded it onto the lenses.

As I did this, Alex held my HoloLens in the air and pointed it at the coffee table behind us. That way, he said, the stage would appear to be sitting on the table, about 2 meters in front of me.

He detached the glasses and handed them to me. They looked like a pair of industrial-strength ski googles, but felt noticeably lighter than any of the other virtual reality headsets I’ve tried on.

The HoloLens consists of an inner ring that fits over your forehead, and an outer ring containing the electronics, which flips up like a visor. Bray instructed us to put the first ring over our heads “like you’re putting on a baseball cap,” turn the knob on the back until we had a tight fit, then swing the 3D display down over our field of vision.

When I looked up, I discovered a surreal 3D image hovering over the coffee table: Two yellow paper airlines were balanced at an angle on stacks of paper cubes, which were themselves perched on top of a large legal notepad. Two paper spheres floated above the scene; one looked like a crumpled ball of newspaper and the other looked like the Everlasting Gobstopper from Willy Wonka. This was the “stage.”

If you squint, these look vaguely like some of the virtual objects in Project Origami (Aaron Muszalski, Dan Morelle, and Zoomar/Flickr).

Beyond this surreal vision, I could see the ghostly outlines of my fellow scruffy journalists through the glasses and hear the person next to me chatting with her mentor.

I poked at the vision in front of me; my finger passed harmlessly through it.

Beyond the 4th dimension

Then we took off the glasses, returned to Visual Studio, and added gaze, gesture, and voice recognition to the stage. Our gaze interface was a red hexagonal ring we positioned by staring at the virtual objects we wanted to control; Bray called this “the donut.” The gesture was a small movement of my index finger, kind of like clicking a mouse button (the “airtap”).

We downloaded the new commands and put the glasses back on. Now when I stared at one ball the donut appeared over it; flipping my finger caused it to drop down onto the surface of the paper airplane, bounce off the edge of the legal pad, and disappear into the 4th dimension, never to be seen again. Saying the word “reset” brought the balls back into position so we could repeat the experiment.

Then we added another voice command, which Bray urged us to customize. Now I could cause the sphere to move by gazing at it and saying, “Drop it like it’s hot.” The next step was ambient sound: We attached a single line of code (“SpatialSound.play ‘ambience.wav’”) that added a cheesy Japanese soundtrack, the kind you’d hear in an airport sushi bar. The sound was location-aware; the closer I came to the stage, the louder it got.

Next was spatial mapping. We added a wireframe to the scene that automatically adhered to the real-world surfaces beneath the virtual one. Now when the ball dropped off the edge of the stage, it bounced off the wireframe covering the coffee table and onto my shoe. Then we removed the wireframe, so it looked as if the balls were reacting to the actual objects in the room. This is when the hairs on the back of my neck started to rise.

We added a command that let us tap on the stage, “lift” it with the donut, and place it anywhere else in the room. This didn’t work so well, but was cool nonetheless.

A virtual heart displayed via HoloLens (Case Western University/Microsoft).

For the grand finale, we added a script that caused the stage to explode when the ball landed, creating a virtual hole in the floor that revealed a subterranean 3D world.

It looked like a scene from Minecraft with the sharp edges sanded off. A red origami crane floated serenely between fluffy white clouds over green fields and twisty blue rivers. When I leaned far enough over the edge of the virtual hole, I could see the ball was still down there, rolling round.

Then I took off my glasses and watched a roomful of scruffy tech journalists leaning, crouching, poking, and tapping … nothing at all.

The revolution will be virtualized

Though impressive, my HoloLens experience was far from flawless. The vertical field of vision was extremely narrow; moving my head even slightly caused the Project Origami stage to disappear from view. Picking up the virtual stage and dropping it seemed to max out the hardware’s ability to render the image — it kept getting “stuck” on various pieces of furniture. And the cartoonish Project Origami was far less sophisticated than the virtual 3D models of bodies and buildings Microsoft displayed during the keynote address the day before.

On the other hand, I was navigating a friggin’ virtual world inside the real one. Hello 2015, your future has arrived.

As we went through our paces, I tried to pump Alex for information about the HoloLens. Every question I had about the hardware — like how many front-facing cameras it had (I counted at least six) or how it did eye tracking — was met with the same response.

“Information was yesterday presented in keynote,” he said. “I am not more to speak of it.”

The woman on stage during the Build 2015 demo is real; the dino skull can only be seen via the HoloLens (Dan Tynan/Yahoo Tech).

The secrecy and security surrounding the HoloLens shows just how important this device is to restoring Microsoft’s mojo. The idea that the world around you can be your computer display — or that you can essentially bring your own holodeck wherever you go — is pretty compelling. The notion that Microsoft Windows is the engine that could make this happen would have seemed laughable less than a year ago. And yet, that future seems to be here — or at least, it will be, if and when HoloLens becomes commercially available.

At the end, Bray urged his audience of crusty old journalists to shout, “We love holograms!” — which they did with the kind of enthusiasm you usually only see from twenty-somethings at Apple events.

Maybe that pupilometer was more effective than I thought.